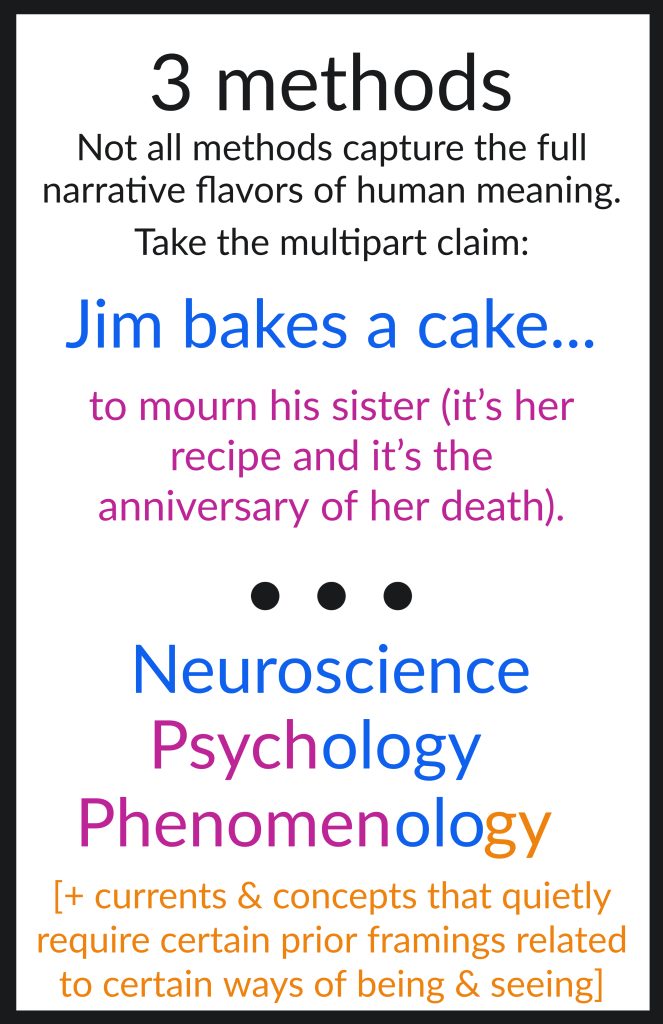

Different analyses require different kinds of tools

(or: Why science can’t tell us everything…)

Empirical sciences like neuroscience and psychology can tell us all kinds of things based on different kinds of data– MRI and other bio-brain data on the one hand, and behavioral data on the other.

But there are often ‘meaning’ flavors that can’t be captured by either MRI data or the data of observed behavior. Take the example of the situation “Jim bakes a cake.”

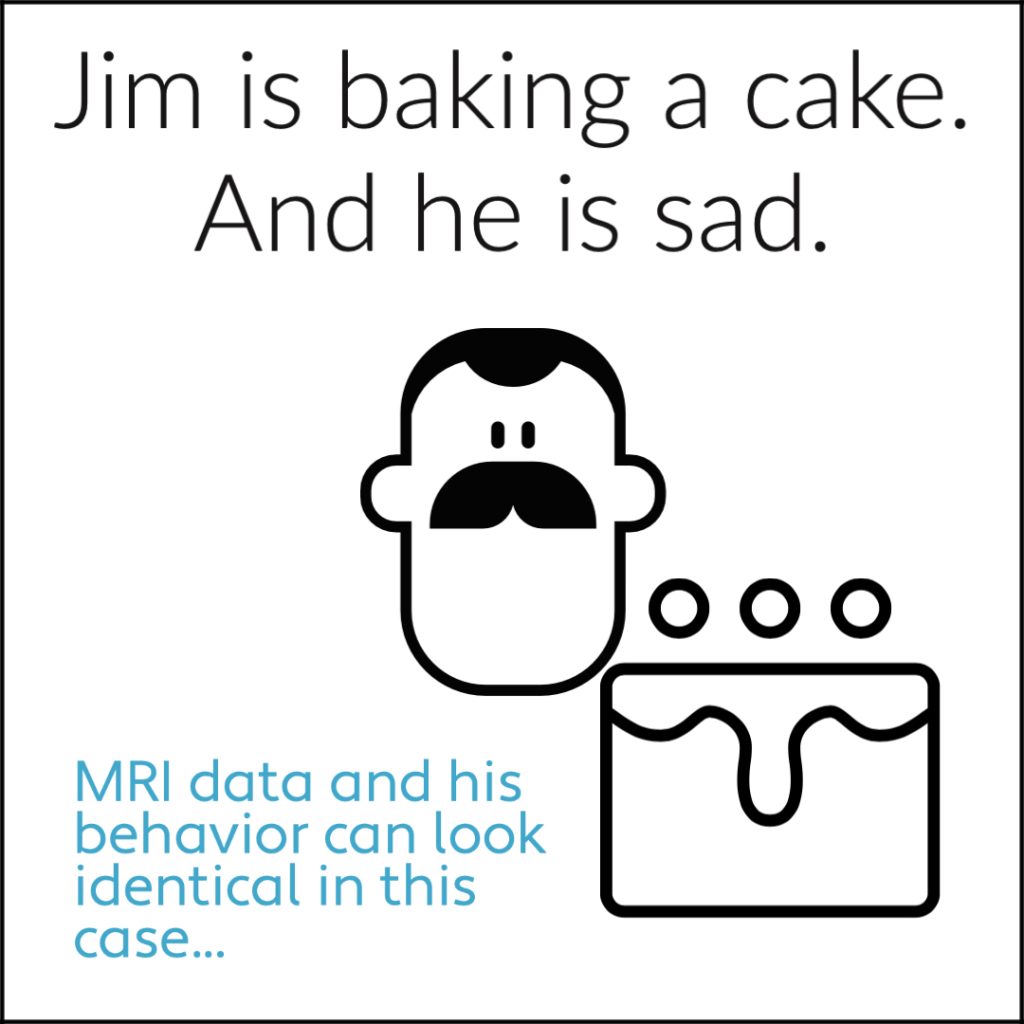

Sure, neurologists and behavioral psychologists can help determine if Jim is happy or sad while whipping up his latest pastry: One can base this on brain waves and the other can base it on Jim’s own reported feelings and actions.

But they can’t really “measure” the difference between Jim “baking while sad” and Jim “baking while sad in the specific sense of baking his sister’s favorite red velvet cake recipe on the one-year anniversary of her untimely death.”

Consider the following three scenarios–MRIs or observed behavior alone can’t always show us the difference between these…

When it comes to certain “flavors” of detail, MRI data or observed behaviors are not nearly “fine-grained” enough to get us the nuance we need–for example, they can’t always help us distinguish “any old kind of baking while sad” from the very particular version of sad-baking Jim is actually undergoing.

Sure, Jim can mention the details–but if Jim is not himself aware of why he is sad-baking, it is not clear that neuroscience or behavioral science are even the sorts of methods capable of unearthing the fuller story.

Consider, though, methods that take us further into the subtler, messier contours of human meaning-making spaces. In the field of psychology, we may point to methods of psychotherapy or existential analysis which precisely set out to “unearth” hidden variables (in this case, Jim’s connection to his deceased sister) in ways that can help us think of ourselves in entirely new ways.

Outside of the field of psychology entirely, there is also a philosophical method called ‘phenomenology’. Appearing in different forms (in, e.g., Kant, Husserl, Heidegger, and Levinas), phenomenology is a non-psychological method of meaning-analysis that also helps “uncover” a given situation’s “hidden background conditions”. Essentially, it is a way of “reasoning backwards” from a given situation (perhaps a concept, a word, a meme, an activity, or even a political movement) to some of the structures, logics, and details that would essentially have to be operating in the background to even allow the situation in question to have manifested in the first place.

When it comes to Jim’s sad-baking, we can compare these methods with these more limited empirical methods:

Here, we hook up Jim to electrodes or pop him into an MRI and we can tell you all kinds of data about what is / not firing and how much of what is secreting and doing things in the brain, body, and neural pathways. But we can’t necessarily see a difference in brain wave or related activity from when Jim is baking in a sad mood because he had a bad day at work vs. when Jim is baking in a sad mood related to remembering his sister–and certainly not between the mood he is in while baking-and-memorializing-his-sister versus the mood he is in while baking-and-memorializing-his-sister-one-year-after-her-passing. Neuroscientific data is not the kind of data that can even hope to parse these different “meaning states.”

Here, we study Jim’s behaviors and self-reports, including his self-reports about his hopes, frustrations, and feelings. And perhaps once we learn that Jim was baking in a sad mood, perhaps we don’t really get into why he was sad–perhaps we just help him find more ways to make time for ‘sad baking’ if that’s what he is looking for, or perhaps we instead help him find more ways to spend less time ‘sad baking’ it that’s his goal instead. We can likely put some concrete strategies in place to help him enhance, deepen, revise, or change his behaviors–and depending on the details, we can imagine that details of Jim’s deceased sibling might not even come into play. We focus on behaviors and we arrive at strategies–perhaps involving pharmaceutical aids, or perhaps working on other strategies entirely–to help get more of the behaviors that we want to see.

Consider this quick visual take on the limits of empirical methods in this regard–the blue color indicated in the methods named below indicates that method’s ability to track the reality of “Jim bakes a cake”, while the pink letters indicate a further capacity to analyze and relevantly engage the fuller reality of why Jim is sad-baking in this particular case of pastry-production. The orange adds yet a further dimension that phenomenology brings to the table.