biblical angels, musical thorns, and memory

from Nietzsche to Levinas

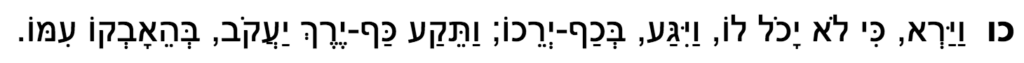

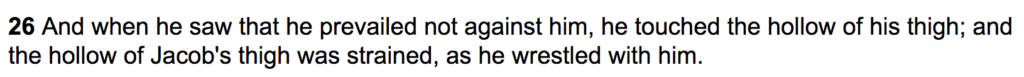

| In which Jacob wrestles with an angel (Genesis 32:26), the “gid hanasheh” goes off limits (or: a jewish farewell to filet mignon), Levinas wrestles with Nietzsche on the merits of forgetting, and UNKLE line 26 looks for the rain with a “thorn in the side.” |

A Thought:

Overcome with torrents of memory, we are looking for the rain to fall. To wash away some of the memories, some of the pain, some of the weight. To release us from our ownmost Jacobian wrestlings. To find the solitude of freedom and the freedom of solitude.

[A pain in the side in Gen. 32:26 as Jacob is struck by a warring angel and in line 26 of our song (to which you can link below) in which we look for the rain with a “thorn in the side”]

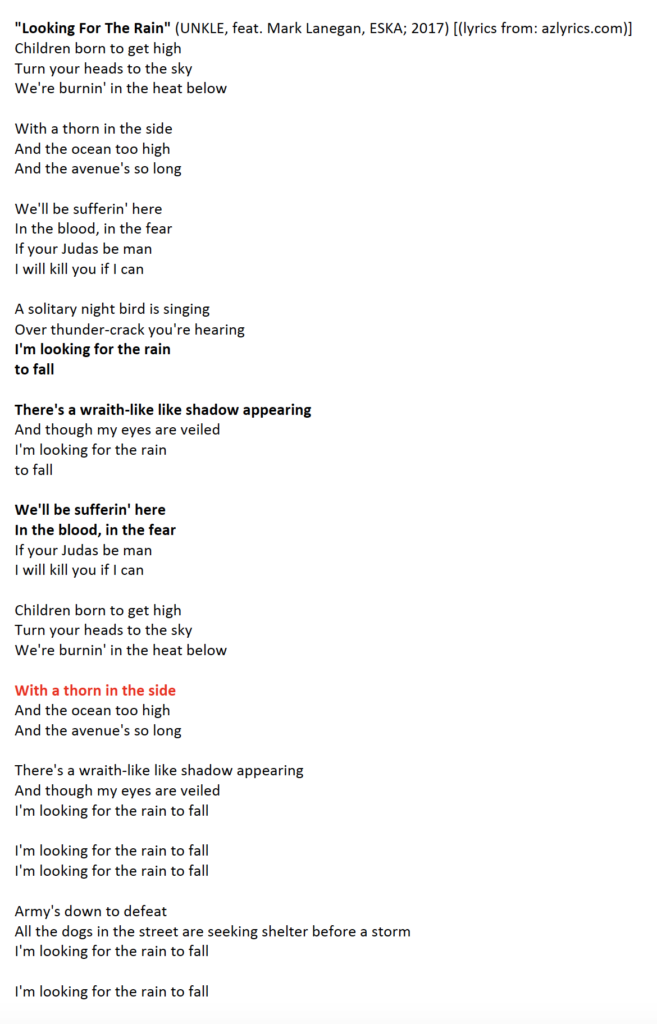

Speaking of the gifts of forgetting Nietzsche is the rain-maker:

‘…that he cannot learn to forget but always remains attached to the past: however far and fast he runs, the chain runs with him. It is astonishing: the moment…returns…as a spectre…Again and again a page loosens in the scroll of time, drops out, and flutters away—and suddenly flutters back again into man’s lap. Then man says ‘I remember’ and envies the animal which immediately forgets…’

– Nietzsche, On the Advantages and Disadvantages of History for Life

But to this hope for rain (as a hope to be an animal and to outrun the ghosts of memory), Levinas brings the weight of human being.

The result? The emergence of a self responsible for the Other and responsible to the pasts we share. We can hope to escape pasts together towards better futures; but simply “getting over” the past on our own regardless of what our neighbor has suffered is a kind of selfishness that can prevent justice. We can’t tell our neighbors to “just move on” just because we might be ready to. While Nietzsche invites us to radical new openings, Justice demands memory.

To be sure, some forgetting is needed. But if we tempt ourselves to taste a freedom that forgets our inter-human debt, then we have unrooted ourselves as humans.

There’s a wraith-like shadow appearing— and that’s the primordial debt that I already owe you and that invokes me and gives me life. When the specter calls, we have found ourselves. No need to envy forgetful finches (here we ought take guidance instead from the [tumbling] elephant who never forgets).

So what’s this about no filet mignon?

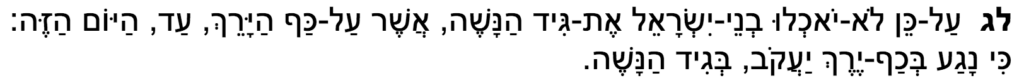

In Jewish tradition, the filet mignon is off limits for a host of intertwined symbolic reasons. One reason: When Jacob wrestled with an angel, he “prevailed” but was hit in the “hollow of the thigh” in the “gid hanasheh” (the nerve in that part of the thigh) which is in the filet mignon; the Torah prohibition follows at 32:33:

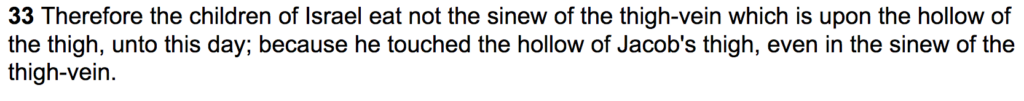

Really? What is this about? Hopefully this: That in Hebrew the term “gid hanasheh” is linked to the term for forgetting, as can be seen, e.g., in Gen. 41:51’s etymological comment on the name “Menasheh”:

| Reading ‘don’t eat filet mignon’ in its (hidden) Hebrew emphasis on forgetting, we can move from ‘don’t eat filet mignon’ to a reminder of the dangers of forgetting–the dangers of following Nietzsche into the hope to be a carefree animal with no remaining weight. In ‘don’t eat filet mignon,’ we move from a desire to sink our teeth into beastly being (yum, steak!) to a symbolic reminder of when Jacob was hit in the ‘forgetting nerve’ in his own moment of victory… …and with Levinas, we can amplify: In times of human victory (in all ages, and certainly today, times when we most celebrate with feasts of meat), we are tempted to forget our human roots–we are tempted to cleanse our bodies of all its hauntings, to fulfill our Nietzschean desire to “go animal” in a cleansing downpour of forgetting as we sail forward–alone, confident, solitary, triumphal. Without a care for the Others. |

But enter the injunction: Do not forget the root/nerve that gives you life; do not forget the others and your primordial, irreducible, grounding responsibility to them. Wrestling with the Others is more human than the ‘winning’ that frees one to a life lived in service to no one but oneself.

Levinas’ point is not for humans to suffer. No one should be contained to a life of constant struggle–with oneself or with one’s others. (On the contrary, Levinas theorizes the home and one’s partners and friends as the spaces in which one is able to live and breath in enjoyment). He calls on us to find care and respite in a homebase (a spiritual and social home, beyond just a georesidence) but all the while to retain a trembling comportment and commitment to the infinite tasks of social justice at hand.