A quick fact sheet.

Julius Evola (1898-1974) is an anti-liberal associated with Italian Fascism. He is being cited by Bannon, so he’s worth worrying about.

Learn more about Evola’s overall views by clicking on this box here:

But is he a racist? Ummm…Yes.

Evola Reading Shelf

(page refs above and below are to these sources):

De Grand, Alexandr. 2004. Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Furlong, Paul. 2011. Social and Political Thought of Julius Evola. New York: Routledge.

Gordon, Robert S. 2012. “Race,” chapter 16 in The Oxford Handbook of Fascism, ed. R.J.B. Bosworth, 296-316. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hakl, H. Thomas and Godwin, Joscelyn. 2019. “Julius Evola and Tradition,” in Key Thinkers of the Radical Right: Behind the New Threat to Liberal Democracy, ed. Mark Sedgwick, 54-70. New York: Oxford Academic.

Sheehan, Thomas. 1981. “Myth and Violence: The Fascism of Julius Evola and Alain de Benoist,” Social Research 48(1) [On Violence: Paradoxes and Antinomies; Spring]: 45-73.

Staudenmaier, Peter. 2020. “Racial Ideology Between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: Julius Evola and the Aryan Myth, 1933-43,” Journal of Contemporary History (JCH) 55(3): 473-491.

Teitelbaum, Benjamin R. 2020. War for Eternity: The Return of Traditionalism and the Rise of the Populist Right. Penguin Books.

With that said, scholars debate the relationship between Fascism and Nazism in general, and in relation to racism and violence. No legitimate scholar denies that both in point of fact led (and can again lead) to deep racism and violence. That said, there is ongoing scholarly debate.

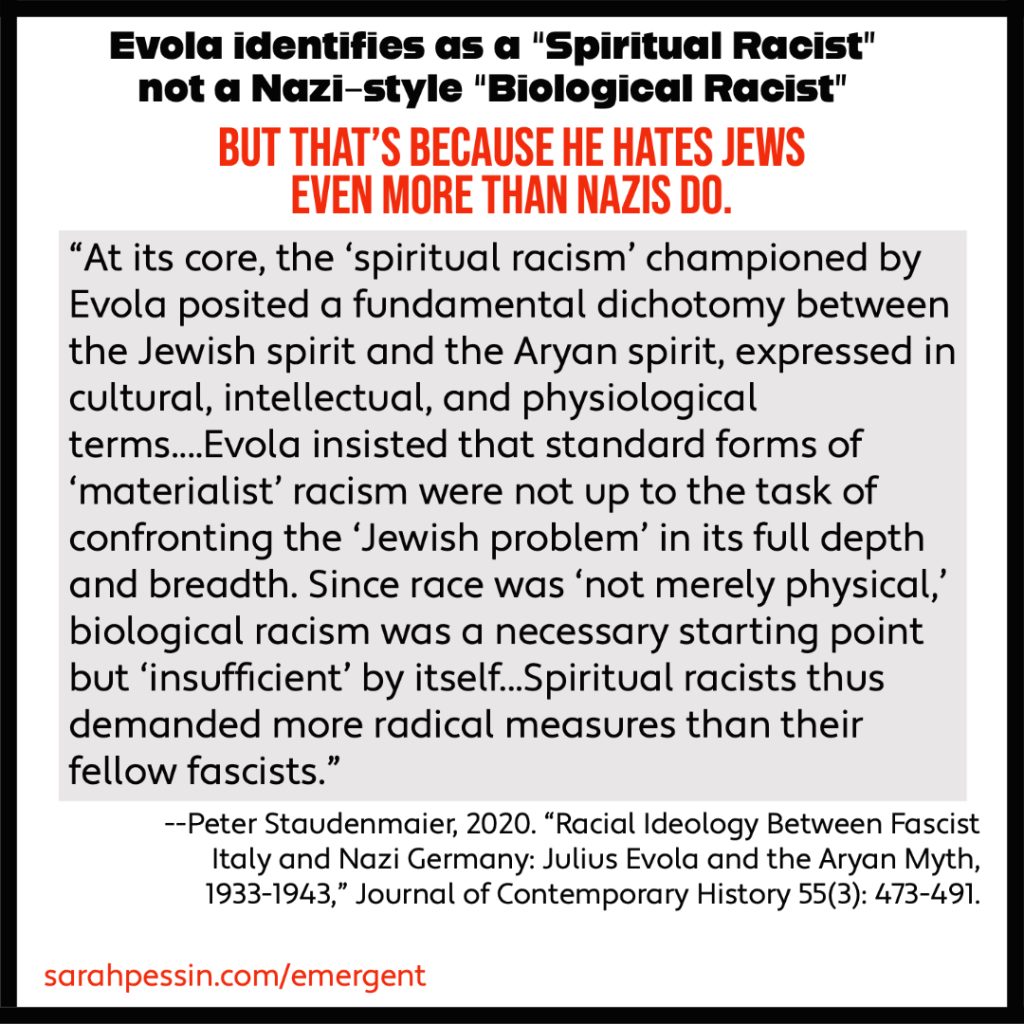

In this regard, Hakl and Godwin, emphasize in Evola a “spiritual racism” opposed to Nazi-style bio-racism, nationalism, and over-emphasis on ‘the Volk’. While Evola tips his hat to Nazism’s show of discipline, he thinks it went bad because it was not, in the end, in touch with the transcendent.

Mirroring this “spiritual” v. “bio” racism distinction, Sheehan 1981 notes: “Although [Evola] never joined the Fascist Party, he was an ardent supporter of Mussolini and enjoyed the dubious privilege of having [Mussolini] endorse his book, Synthesis of the Doctrine of Race (1941), as the official statement of Fascism’s “spiritualist” racism as against Nazism’s merely biological racism” (Sheehan 1981, 50).

In line with this sort of distinction, and mindful of the “extremes of racial violence” that Hitler’s and Mussolini’s regimes both enacted, the Oxford Handbook reminds us of–even as it challenges–a longstanding distinction in various writers between Nazi views of race and Fascist view of race: “Whereas Hitler’s Germany was centrally structured around a racial or racist ideology, a form of ‘Aryan’ anti-Semitism, Mussolini and the Italy of the ventennio were only marginally and latterly interested in questions of race, and then only for contingent or tactical reasons to do with Italy’s political alignment with Nazi Germany. If the former was a ‘racial state’, the latter – even as it pursued, at times, an aggressive politics of race – was not,” (Gordon 2012).

That said, Gordon ends by recommending that there are deeper racist aspects to fascism. In this regard, Gordon also cites historian Alexander De Grand’s note to the 2004 edition of his earlier 1995 analysis; De Grand writes: “Both Hitler and Mussolini aimed at re-educating their respective societies according to an entirely new set of values that would be a repudiation of the humanitarian and rationalist tradition of the Enlightenment in both its liberal and socialist form. Nowhere is this rupture more apparent than on the issues of creating a new community and racial policy. Since completing the first edition [of this book], I have come to believe that the divergence between Fascism and Nazism on racial policy is not as great as I believed. Both regimes used race partly as an instrument in the realization of a totalitarian state. If this is true, then Italian Fascist racial policies during the late 1930s were not an aberration or an attempt to align Italy with Nazi Germany, but a logical extension of the essential nature of the regime,” (De Grand, 2004, 2–3).

Along these lines, consider Benjamin Teitelbaum’s account of Evola: “In addition to a hierarchy with spirituality on top and materialism at the bottom, Evola proposed that race also ordered human beings, with whiter, Aryan people constituting a historical ideal atop those with darker skin–Semites, Africans, and other non-Aryans…[S]pirituality, antiquity, Aryan or white race, masculinity, the northern hemisphere, sun worship, and social hierarchy are all intertwined…This informed Evola’s understanding of history: he believed that Aryans were descended from a patriarchal society of ethereal, ghostly beings who lived in the Arctic and whose virtue declined as they migrated south and became incarnate…,” (Teitelbaum 2020, 12-13).

Consider too Paul Furlong’s analysis: “[Evola’s] undoubted opposition to biological racism only covered the first term, not the second. He had a particular conception of racism that rejected a crude unscientific biological causality in favour of a spiritual determination, but that does not mean he did not ascribe to a form of racism,” (Furlong 2011, 115)